CROSSROADS

By Chris Wadsworth

Color aerial photos by Vantage Point Drone

“I remember everything being quiet — everything except the birds and the insects.”

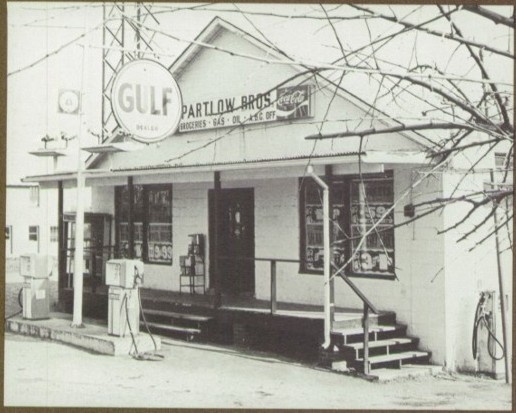

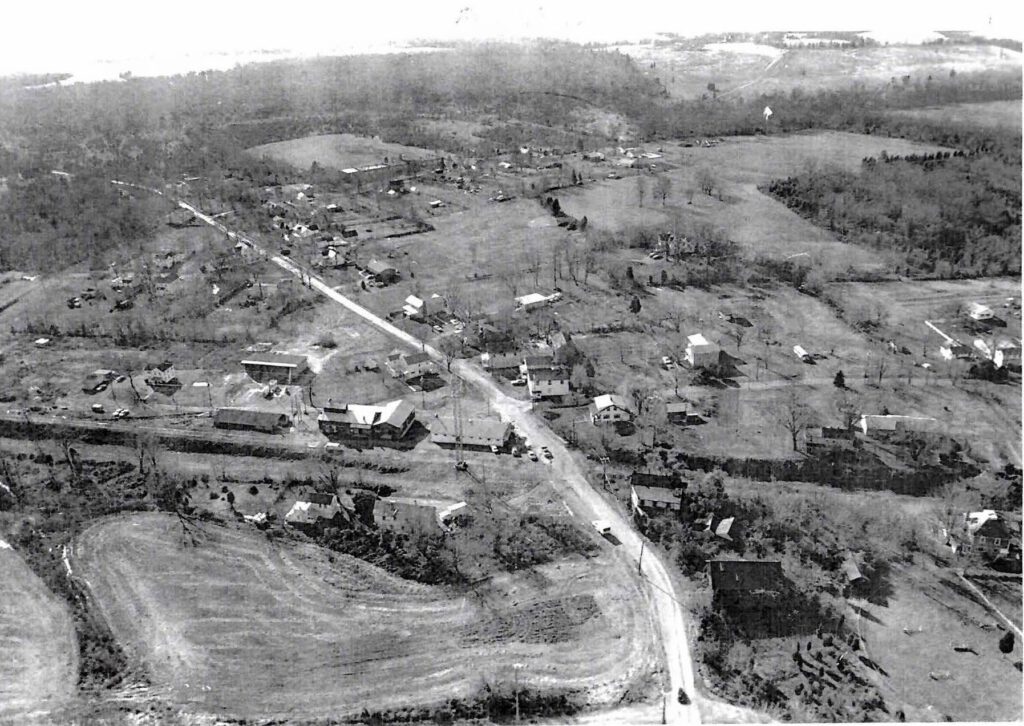

That’s how lifelong Ashburn resident Randy Poland describes growing up here in the 1950s and 1960s. It was the quintessential rural life — dairy farms, gravel roads, a general store, a single brick school.

But in 1985, when Poland turned 30, Ashburn also reached a crossroads. That’s when county leaders approved a new development that would fundamentally change this tiny dot on the map forever. The development was called Ashburn Village — a neighborhood filled with 5,000 homes, dozens of new roads, a supermarket and shopping center and much more.

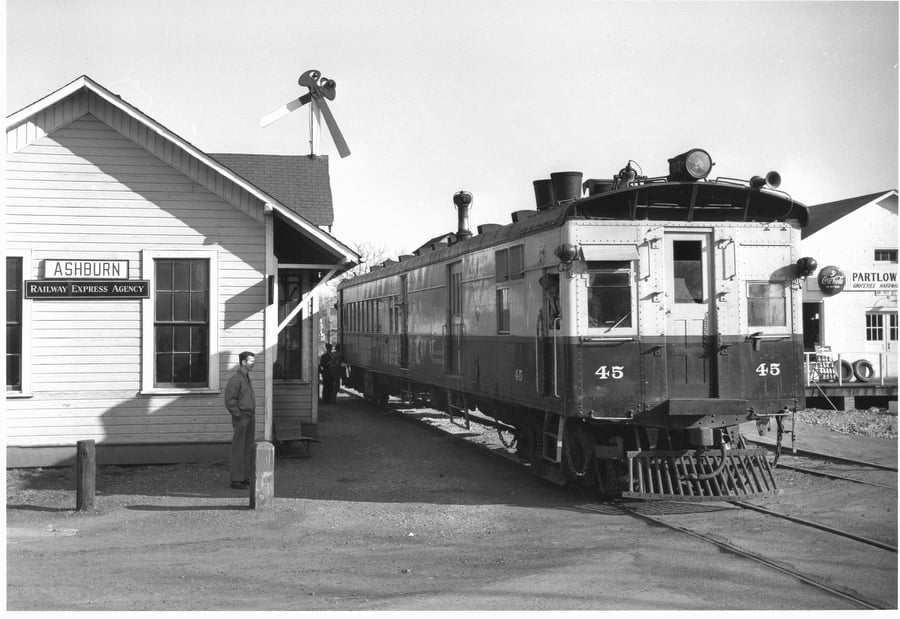

A headline that year in the Washington Post read, “Neighbors Uneasy About Impact of Ashburn Project in Loudoun.” Uneasy to say the least. The green light for Ashburn Village dominated conversations at dinner tables, church suppers and at the local store. Change was coming.

In October of this year, three historic buildings along Ashburn Road were torn down to make way for a new residential development. One of those buildings was Randy Poland’s childhood home — showing that the change that started 35 years ago with that fateful vote is still occurring today.

FEARS

“We’re not the least bit ambivalent about it. We’re dead set against it.” That’s what Ashburn resident Robert Gullo told the Post in the December 1985 newspaper story about Ashburn Village. Gullo had moved his family from Annandale because he liked the open spaces and country living. “Hell, I commute an hour and a half each day just to live here.”

Gullo and those on his side of the debate loved the rural lifestyle. They could work in Washington or the nearby suburbs dense with office buildings, then head up Route 7 and travel back in time — past the quickly growing communities in Fairfax and the new neighborhoods crossing the county line into Sterling — into the country that still looked much as it had a century before.

Another one of the locals quoted in the Post article was Sterling activist Stanwyn Shetler. Shetler lived in Loudoun County until his death in 2017. His daughter, Lara Shetler, says her father was a life-long environmentalist who was frustrated with how Ashburn’s green spaces were disappearing — something local residents still complain about.

“I think dad has always known that growth was inevitable, especially in this area, but he strove for … growth and nature to [go hand in hand],” Lara Shetler said. “The developers come in and completely bulldoze an area down. They don’t save any of the trees, or any of the little habitats that might have been unique to the area. And then they put some trees back in, and they might not even be trees appropriate to the area.”

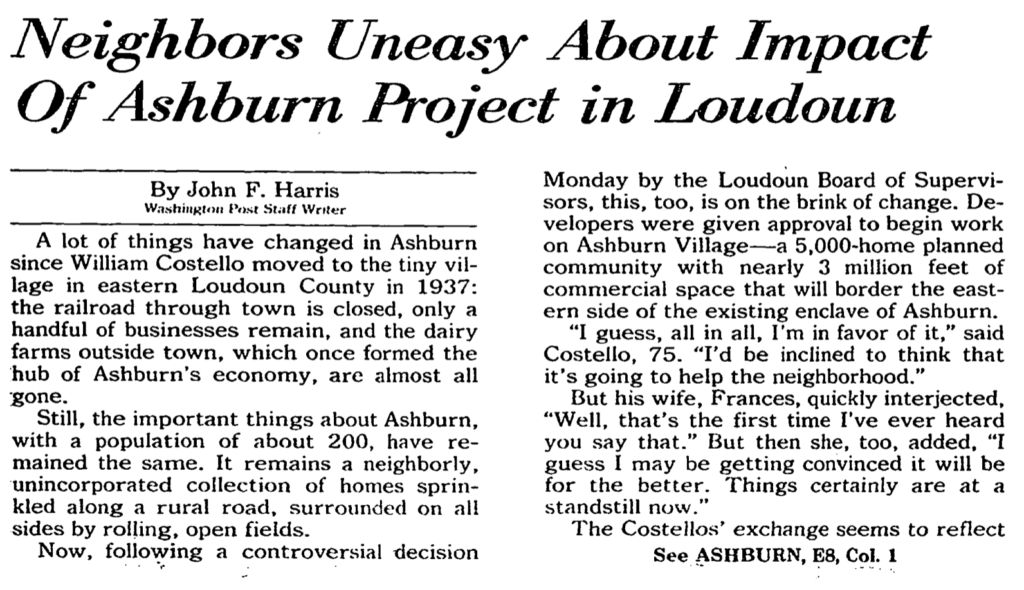

Back then, Partlow’s Store was pretty much the only shopping in Ashburn. That’s the building next to the W&OD Trail where Carolina Brothers BBQ is today. Locals called it the “Ashburn Mall” because you could buy more than just your staple groceries. You could also shop for shoes, boots and other essentials.

Cathy Cox grew up in Ashburn as well, right along Ashburn Road. She says Partlow’s was more than just a store — it was a hub of the community.

“Calvin and Ernestine Partlow … helped people out the best they could in any way possible,” Cox said. “The store had a variety of everything. Calvin butchered meat for his deli section along with having shelves stocked from foods to hardware supplies. Gas, air and kerosene were also available. The Partlows were well respected in our little town.”

Community traditions stretched back generations — the annual Ham & Oyster Dinner at the Ashburn fire house, the Turkey Shoot contest, the Fireman’s Parade & Carnival. Area churches had events called “homecomings” — potluck dinners where every family tried to outdo the next to see how much food they could bring.

And there was a sense of community spirit. That everyone was in it together.

“If there was a death in the family, there would be more food at your home in a day than you could eat all year,” Poland said. He recalls a blizzard that once swept in, leaving Ashburn Road in deep drifts. Local men dug out Ashburn Road all the way north to Route 7 so the milk trucks could get out.

“It was such a small community, we had to count on each other for help.”

This is what Ashburn Village threatened. How could a tiny, tight-knit community of 200 people absorb 5,000 new homes and 5,000 new families, along with new stores and roads and businesses without something — everything — changing? They answer is they couldn’t — and they knew it.

HOPES

But the rolling hills and the corner store were only half of the picture of Ashburn in the mid-1980s. There was another side as well — one that led some people to hope Ashburn Village would bring new life to a community that many felt had been dying for years.

The red clay soil in Ashburn had never been great for farming crops. Locals say it didn’t grow much, but it produced enough for dairy cattle to munch on. Indeed, dairy had been the mainstay of the local economy since the 1800s. But by 1985, many of the local farms had shut down and were vacant.

“Farmlands were being bought out for development. Dulles Airport took out hundreds of acres, and that was the start of it all. That is why so many of us left Loudoun County and moved ‘over the mountain,’ as we say,” said Cox, who moved for a time to Clarke County with her family.

Indeed, older residents were dying and others were moving away, and there just weren’t younger families coming in. During this time, Tillett’s Auction Barn — which still stands off Belmont Ridge Road — was busier than ever.

“One of the big things at that time was farm auctions — families getting rid of their stuff. Most of the farms had sold out or were getting ready to sell out,” Poland said.

And for the residents who did live here, things weren’t always easy. Roads were often gravel and filled with potholes. Homes were on septic tanks. Ashburn Village came with a promise from the developers to bring sewers to area homes and new, wider paved roads to the community — something Ashburn may not have merited otherwise.

The Shetler family lived in the Sugarland Run neighborhood in Sterling, and Lara Shetler attended Broad Run High School. “Driving to the high school or taking the bus — it was a potholed back road,” she recalled. “It was paved, but it was more gravel than pavement.”

For real shopping — supermarkets, clothing shops, record stores — locals had to go to Herndon or Leesburg. Same if they wanted to cool off in a swimming pool or see a movie.

“There was nothing between Sugarland Run and Leesburg. It was just wide open. They had a light at Route 28, and it was a flashing light,” Lara Shetler said. “If you wanted to go to a mall you went to Tysons or Fair Oaks. There was nothing close by.”

Sure, Ashburn Village brought the promise of change — but at least some of that change was something many in Ashburn desired.

“I guess I may be getting convinced it will be for the better,” Ashburn resident Francis Costello said in the 1985 newspaper article. “Things certainly are at a standstill now.”

And to this end, Poland says there wasn’t any serious movement to try to stop Ashburn Village.

“I think a lot of people just felt it was inevitable. They saw Sterling Park coming in and Sugarland Run and Cascades. It was just moving in this direction,” he said. “There wasn’t anybody that lived in Ashburn that held enough power politically to do anything about it.”

REALITY

Once the Ashburn Village deal went through, change started quickly. Calvin Partlow sold his store. New owners kept it operating, but one of Ashburn’s most prominent citizens had given up the ghost. It was a sign.

“When it all started, the traffic really picked up on Ashburn Road. My father couldn’t back his car out without having to wait,” Poland recalled. “He came in and said, ‘We’re moving.’ And we moved.”

The Polands’ home with its bricks and columns and white porch — the one his parents had paid $6,000 for in the 1950s — sold for half a million dollars. Today, it’s a vacant lot waiting to be built upon.

Nearly all the area farms were eventually sold. Eventually, a new kind of farm appeared in the area — data farms. Where the greater Ashburn area was once known for dairy farms, today we are famous around the world as “Data Center Alley,” one of the critical hubs on the internet.

“Ashburn is a real success story,” said Buddy Rizer, executive director for Loudoun’s Department of Economic Development. “The county has taken a proactive stance on building communities like Ashburn out in a planned fashion, even as the population has grown as fast as anywhere in the U.S. That includes reserving tracts of land for schools, libraries and community centers while recognizing the opportunity that data centers present in lifting the tax burden off of residents.”

Meanwhile, back in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the staples of the community began to buckle under the pressure of thousands of new families. In 1991, the tiny Ashburn post office closed after serving the community for decades. It stood near the W&OD Trail by the fire station, but the building is no longer there.

In 1992, the new Ashburn Elementary School opened, replacing the old 200-student school that had served Ashburn since 1945. The original school still stands on tiny Partlow Road and is used as a staff training site for Loudoun County Public Schools.

“When you take the post office and the elementary school out of town, you don’t have much left,” local resident Steuart Weller said in another Washington Post article in 1991. Weller was the owner of Weller Tile & Mosaics, once based in Ashburn. A local elementary school is named after him. The building that once housed his business was among those torn down in October.

Ashburn Village was followed by Ashburn Farm — then Broadlands, Belmont Greene, Belmont Country Club, Brambleton and many more.

The change that started with Ashburn Village turned out to be exactly what those long ago residents had feared — and hoped for. The beloved annual events did disappear — no more oyster dinners or turkey shoots. The sense of a small-town community did change, because Ashburn isn’t a small town anymore. But there are roads and sewers, not to mention restaurants and movie theaters and swimming pools and shopping centers — things an Ashburn resident of 1985 could have scarcely imagined.

Whether all the change is good, bad or otherwise is up to each individual.

“I would love to see the old train come through again and the engineer wave at us [and] see those old-timers back on the Partlow store’s porch having their conversations,” said Cathy Cox. “Those were some of the best days of my life.”