THE HUNT FOR THE LOST CLIPPER

By Chris Wadsworth

In October 2021, a meeting was held in a private dining room at the Clyde’s Willow Creek Farm restaurant in Ashburn. The men who gathered are part of a team that has been slowly and carefully assembled over two decades. They are a band of brothers devoted to solving one of aviation’s most enduring mysteries — a mystery that stretches around the world to the middle of the Pacific Ocean — and the quest has its roots right here in Ashburn.

It’s called The Hunt for the Lost Clipper.

THE ORIGIN

Over the arc of a long career, Guy Noffsinger has worn a lot of hats. Naval intelligence officer, photographer and videographer, NASA television producer and documentary filmmaker. But his latest endeavor feels like something more out of an Indiana Jones adventure.

Back in 2000, Noffsinger — who previously lived in Ashburn and currently lives in Purcellville — was a graduate student at the Joint Military Intelligence College in Maryland. He was working on his thesis, which was going to explore the search for famed missing aviator Amelia Earhart from the perspective of the Navy.

During his research, he came across a non-fiction book by author Charles Hill titled, “Fix on the Rising Sun: The Clipper Hi-Jacking of 1938.”

“I thought it was an amazing story that I had never heard before,” Noffsinger said. “I started going down a rabbit hole.”

Almost immediately, Noffsinger changed the focus of his thesis to explore what turned out to be a mystery stretching back to before World War II — the loss of the Pan Am “Hawaii Clipper” over the Pacific Ocean, with 15 souls on board.

Noffsinger started work on his new thesis 20 years ago — and it’s still not complete.

“I couldn’t get to the bottom of it. I couldn’t answer the questions,” he said. “I knew that I had to go investigate myself.”

And so, he did. Four trips so far to a remote island in the western Pacific. Along the way, he has picked up a team of fellow researchers and adventurers — including several men from Ashburn — who are as determined as Noffsinger to solve the mystery of the Lost Clipper once and for all.

THE MYSTERY

Here is the basic story of the Lost Clipper and as well as the theory posited by Noffsinger, Hill and others.

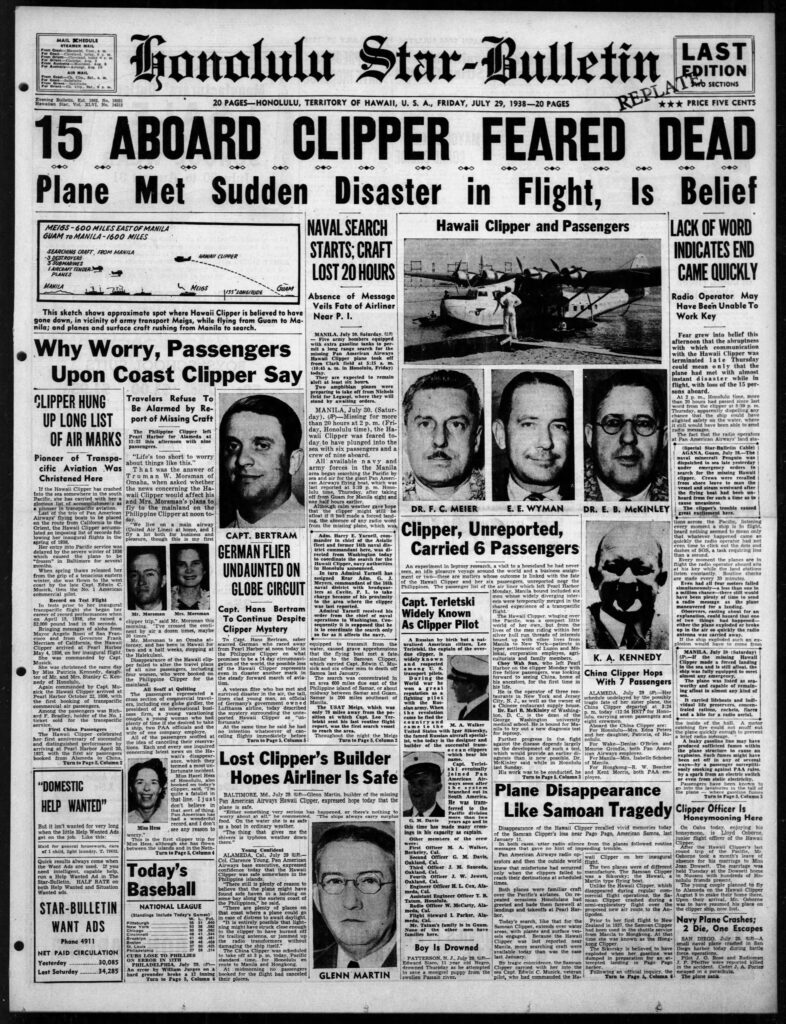

The Hawaii Clipper was a Martin M-130 flying boat, meaning the plane could land on water. It was part of the fleet of Pan American Airways, generally known as Pan Am and, at the time, the largest international air carrier in the world.

In July 1938, the Hawaii Clipper began Trip 229, a regularly scheduled 60-hour flight from San Francisco to Manila in the Philippines. It island-hopped along the way, stopping at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii, then Midway, Wake Island and Guam.

At 11:39 a.m. local time on July 28, 1938, the Hawaii Clipper took off from Guam for the final leg to Manila. Three hours and 27 minutes later, the plane lost contact with radio operators. It disappeared — somewhere over the vast deep blue waters of the Pacific — with six passengers and nine crew members on board and was never heard from again.

A U.S. Army transport ship in the area found an oil slick along the Hawaii Clipper’s path and oil samples were taken, but they were never confirmed to be linked to the lost plane. The official ruling is that the Hawaii Clipper must have crashed — but be it from mechanical failure, rough weather, pilot error, no one knows.

Or do they?

THE THEORY

Based on more than two decades of research, Guy Noffsinger thinks he knows what happened to the missing plane — and believe it or not, it ties to the famous mystery of Amelia Earhart, who disappeared almost exactly a year earlier, in July 1937.

Noffsinger and others believe that at least some of the passengers and crew on the Hawaii Clipper were working for the U.S. government — that they had been told they were on a secret mission to transport $3 million in gold-backed banknotes to organized criminals within the Japanese Navy who were allegedly holding Earhart ransom.

Only it was a ruse, and the Japanese were actually after the new, long-distance engines on the Hawaii Clipper. They feared their own airplanes were less advanced and the new high-tech engines on the Clipper would give the United States an advantage in the run-up to World War II, which was already brewing.

The theory goes that two Japanese hijackers disguised as mechanics crept on board in Guam and hid in a cargo hold. This is based on FBI interviews at the time with Marine sentries who said they gave two mechanics access to the plane in the overnight hours. Once the plane was over the ocean, the Japanese agents took over the plane, forced it to land and took the passengers and crew prisoner.

The prisoners were allegedly taken to Tonowas Island, in the Truk Lagoon, part of what today is called Chuuk Lagoon in the Federated States of Micronesia. There, they were executed and buried in a cement slab, and the Hawaii Clipper disappeared into the mists of the growing Japanese war machine.

THE TRIPS

The theory may sound far-fetched, but there is evidence to support nearly every aspect of it, says Noffsinger. In 2002 and 2004, he traveled alone to Tonowas Island, using the money he raised selling his collection of vintage military helmets. On the island, he interviewed family members of eyewitnesses who relayed stories about the prisoners decades before.

Along the way, he teamed up with longtime friend and Broadlands resident Jeff Riegel, a filmmaker.

“Usually history doesn’t intrigue me, but the way this guy told the story — it was contagious,” Riegel said. “I kind of forced myself on him and said, ‘Hey, do you need some help with this?’”

Help indeed. The two men traveled around the United States — Massachusetts, Florida, New Hampshire, Texas — and to Canada as well, interviewing people with connections to the story.

Then, Riegel accompanied Noffsinger on his third trip to Tonowas in 2014.

“My first impressions were that it was like a third-world country,’ Riegel said. “They hadn’t paved a road since we blew [the Japanese military] up in ’44.”

Based on accounts from locals, the men were looking for that concrete slab. They knew it was roughly 30 feet by 60 feet and oriented so it was pointing north. But there were at least 1,100 concrete slabs scattered around Tonowas — where to start?

Back in Loudoun County, Noffsinger and Riegel were joined by Ashburn Farm resident and political consultant Stephen Clouse, who became fascinated with the story after hearing about it at a backyard barbecue.

“There are two types of history. The history that is known and the history that is not known,” Clouse said. “The more insidious is the history that is omitted. I think [omitting the true story of the Lost Clipper] is intentional and the question is, ‘Why?’”

Clouse soon looped in his friend, a trained law enforcement officer whose name you might recognize: Steve Murphy.

Murphy, a longtime Broadlands resident, is a retired agent with the Drug Enforcement Agency. He was part of the team that hunted and brought down drug kingpin Pablo Escobar. His story was turned into the hit Netflix television show “Narcos.” (Murphy was profiled in the July 2020 cover story of Ashburn Magazine.)

“Going to Miami as a DEA agent in the 1980s was an adventure,” Murphy said. “Going to South America pursuing Pablo Escobar was an adventure. When I retired, the adventures were kind of over. So, this was the start of a whole new adventure.”

Murphy’s DEA partner, Javier Peña, also joined the team. He helped Noffsinger conduct a key set of interviews with the children of one of the lost Pan Am pilots, which confirmed many of the critical details.

Murphy, Clouse and Riegel joined Noffsinger on a fourth trip to Tonowas in 2018. Each trip — coupled with copious amounts of research and interviews conducted in the United States — had helped the team finally narrow down its focus to a specific parcel of land. It was the spot where they believed the bodies of the murdered passengers and crew had been hidden.

The site was a former Japanese military medical dispensary recorded in old photos and maps. It was under construction in 1938. That’s when eyewitnesses had reported the 15 Americans from the Hawaii Clipper were murdered and entombed in concrete as the slab was poured.

The dispensary is long gone, and a house stands on the land today. On Trip 3, the team dug up the floor of the house but found nothing. On Trip 4, they used ground-penetrating radar around the site. It recorded something buried under the earth, but that turned out to be large rocks, not bodies.

The team was stumped until Clouse — who had experience in the construction industry — noticed some remnants of poured concrete next to the house. The men soon discovered that a slab had been there, but it had been bulldozed in 1970 after a typhoon swept across Tonowas.

The team poked around in the overgrown ravine behind the spot and found a set of concrete steps — the same steps that appeared in photos of the old dispensary. They paid a team of locals to spend the night hacking away and removing all the underbrush and vegetation and, when they returned the next day, found a debris field filled with the former concrete slab. If the victims were indeed once in that slab, they were now buried in this field of garbage and old concrete.

Using metal detectors, the team found World War II-era medicine bottles that would have been at the Japanese dispensary and — even more critical — they found a vintage tie pin and buttons consistent with the type worn by Pan Am pilots in the 1930s.

“We were electrified,” Clouse said. “I said to Guy, ‘You’re probably standing only a couple of inches above where they are.’”

THE FUTURE

And now comes the harsh reality of conducting an expedition such as this. The discovery of the tie clip and the steps came on the team’s last day on Tonowas in 2018. When traveling halfway around the world, with schedules and permits and boat rides and flights that happen only on certain days, when it’s time to go, it’s time to go.

Their time on the island was up with no opportunity to follow up on their latest discovery.

So now, the team is back in Ashburn and Purcellville and elsewhere as they work toward what they are calling Expedition 5. This will be the return trip to Micronesia, to the Chuuk Lagoon and the island of Tonowas. This will be their chance to finally pull up those chunks of cement and hopefully find the final resting place of 15 Americans who — one way or the other — were in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Originally, the team was looking to return to the Pacific in 2020, but the COVID-19 pandemic quickly put an end to that. Now, they are aiming for 2022.

Team member Jim Janicki, who lives in the Baltimore area, came up with a plan to aid in the search. A certified search dog handler himself, he is overseeing the addition of several highly trained cadaver canines to Expedition 5 — dogs trained to sniff out bodies, even after 80-plus years. Hiring the dogs is expensive and transporting them halfway around the world, along with their handlers and a veterinarian, adds to the cost. So, the team is working with investors and raising funds to help support the search for the Lost Clipper.

One possible route — strike a deal with television producers to turn the Hunt for the Lost Clipper into a reality TV show.

“Everyone wants to hear a good story and there’s nothing new in Hollywood,” Noffsinger said. “Here is a chance to tell a story no one has ever heard.”

The Lost Clipper team was close to a deal with one cable network, but a rival channel debuted a series that touched on Amelia Earhart. That was too close in theme, and it squelched the deal.

But the Lost Clipper gang is not deterred.

“I feel more excited than I have ever been about this project. More alive. More attuned,” Noffsinger said. “We are this close. It’s like running an endurance race for 20 years and now I can see the finish line. And it’s not just me alone anymore. I’ve picked up an entire team and we’re going to cross that line together.”

The Team

Guy Noffsinger

Purcellville (lived seven years in Ashburn previously)

Founder, Chief Historian

Jeff Riegel

Broadlands

Communications

Stephen Clouse

Ashburn Farm

Strategic Researcher

Steve Murphy

Broadlands (recently moved to Orlando, Fla., area)

Lead Investigator

Javier Peña

San Antonio, Texas

Lead Investigator

Jim Janicki

Phoenix, Md.

Engineer, Technical Advisor

Bob Perry

Boston, Mass.

Ground Penetrating Radar Expert

Ollie Dale

Auckland, New Zealand

Cinematographer

Bill Stinnett

Chuuk, Federated States of Micronesia

Local Subject Matter Expert, Local Government Liaison

Myron Hashiguchi

Chuuk, Federated States of Micronesia

Local Cultural Expert